The Return of General Pike

Celebrating white supremacy at D.C.s Judiciary Square

Last week’s restoration of a Confederate general’s statue in D.C.’s Judiciary Square is an affront to Americans of conscience and galling in the extreme given that no monument to Union victory stands in the nation’s capital, the nerve center of our annihilating Civil War that took some 700,000 lives.

Strewn across Washington are statues to Union generals and discrete groups of veterans, but no single memorial honors the immense sacrifice required to destroy slavery and preserve the Union.

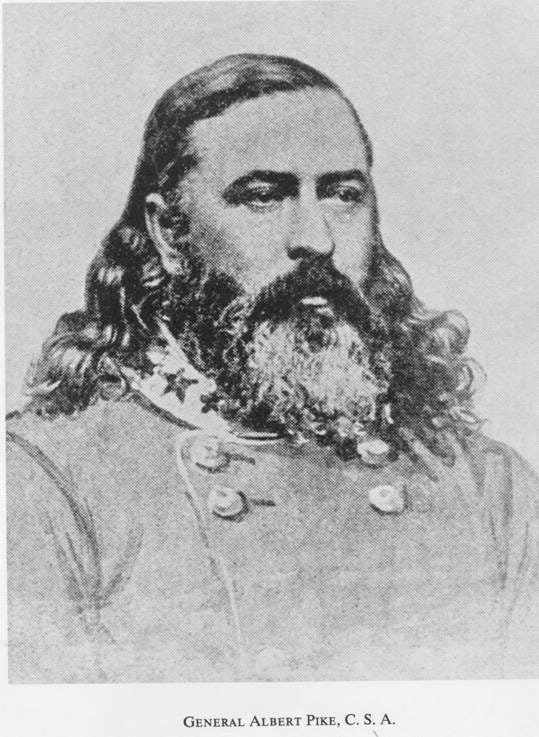

A lawyer, poet, and newspaper man, General Albert Pike (1809-1891), CSA, was a Boston-born southern nationalist who lit out for the American southwest as a young man, eventually settling in Arkansas. A slaveholder, he founded the state chapter of the nativist anti-Catholic Know-Nothing Party and advocated for the expulsion of its free Black people—who he decried as an “evil.”

(Pike walked out of the 1856 Know Nothing presidential convention after the party failed to adopt a pro-slavery platform.)

Commissioned as a Confederate brigadier general in the summer of 1861, Pike commanded the Confederacy’s Native allies along the Arkansas frontier. Reprimanded for lax control over his troops and failure to follow the orders of his superior, Pike abandoned his post, was threatened with treason, and resigned from the army within a year.

Relocating to Memphis after the war, he edited the white supremacist Memphis Daily-Appeal, where he editorially pooh-poohed northern alarm over Klan outrages. Like all aggrieved white southerners, he belligerently alleged that they lived under the humiliating victimization of “superstitious negroes” egged on by the Freedman’s Bureau and Union Leagues. The Klan, he editorialized in April 1868, had not organized nearly so comprehensively as he would have liked; he floated instead his preference for “one great [secret] Order of [white] Southern Brotherhood” to fight “negro suffrage.” If, as his admirers have insisted, Pike was not a sworn member of the terrorist organization, he was surely an ardent fellow traveler.

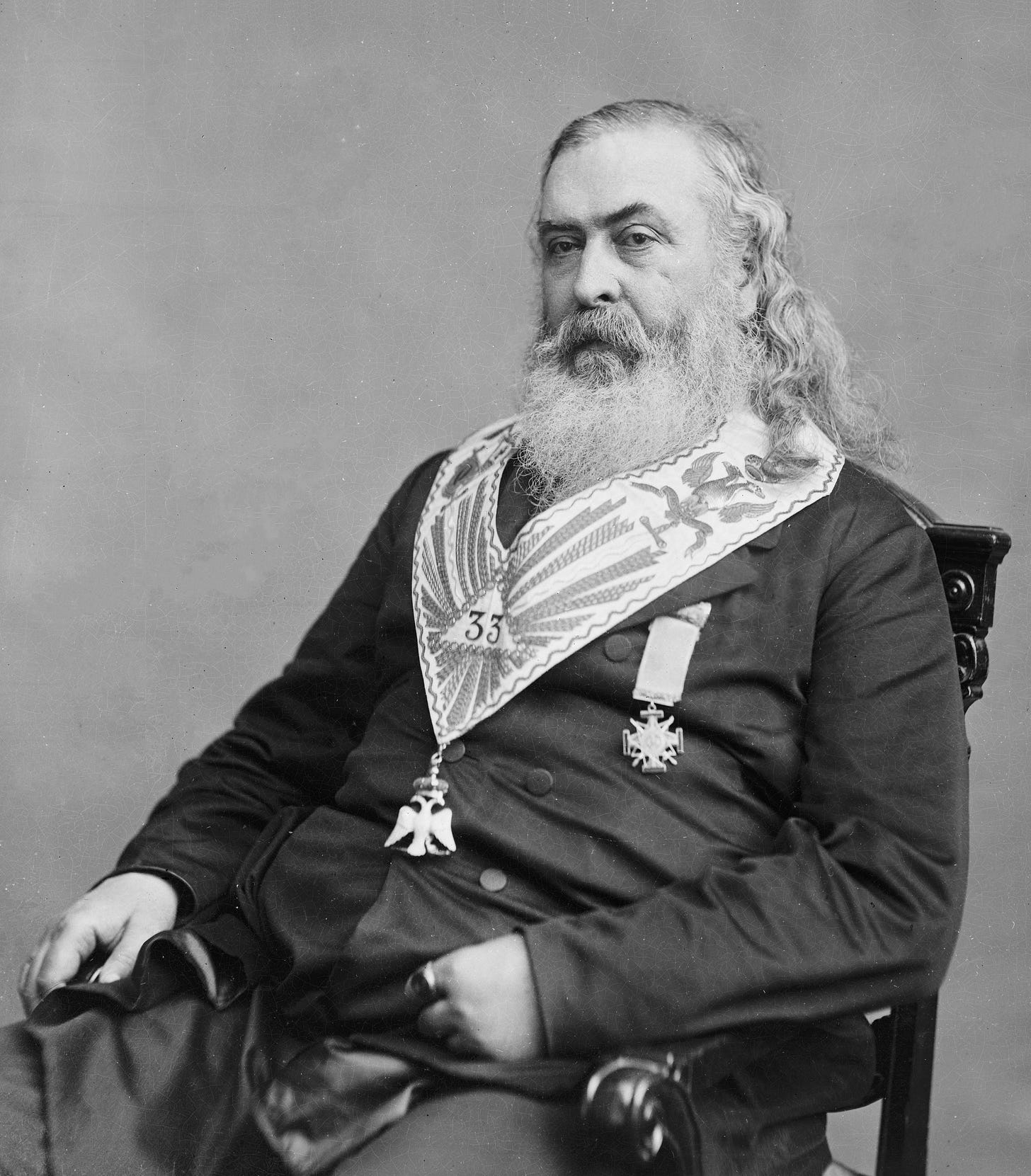

In his last decades, Pike devoted himself maniacally to studying and writing about Scottish Rite Freemasonry in Washington, D.C., rising to the office of its Sovereign Grand Commander. He died in its G Street N.W. “cathedral” and was buried at Oak Hill Cemetery. In 1944, his body was exhumed and moved to the foreboding “House of the Temple” on 16th Street N.W. just beyond Scott Circle.

After years of intermittent protests, antiracists tore Pike’s statue from its pedestal in 2020 and set it ablaze. Five years later, President Trump ordered its repair and restoration under the aegis of his absurdly titled executive order, “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.”

In carrying out Trump’s directive, the National Park Service commented, “The restoration aligns with federal responsibilities . . . to beautify the nation’s capital and reinstate pre-existing statues.”

Beautify?

This is Donald Trump-speak, the gibberish of a latter-day Pike, who regularly and cavalierly misuses the adjective form of “beauty” to describe everything from Pike’s statue (“a beautiful piece of art”), to his garish $300 million ballroom (“a very expensive beautiful building”), to his cult followers (“you beautiful Christians”), and his campaign to plunder the dwindling resources of working Americans (“the big beautiful bill”).

General Pike’s return is no surprise given the dysfunctional tending of Judiciary Square’s monumental grounds, a lamentable history that dates to the genesis of the republic.

George Washington charted this crooked path when he abruptly fired Pierre L’Enfant, the Parisian architect he chose to design the “Federal City.” In his 1791 “Manuscript Plan for the City of Washington,” L’Enfant designated Judiciary Square for the U.S. Supreme Court.

Situated on a ridge that runs north of and parallel to Pennsylvania Avenue, Judiciary Square lies a half-mile northwest of the U.S. Capitol and a mile due east of the White House. L’Enfant sited the three branches of federal power in this elevated terrain as a visible and symbolic homage to the foundations of the new republic.

A trio of Washington’s fellow Virginia land barons and slaveholders resented the Frenchman’s appropriation of land on which to build the new government, despite its promise of a real estate boom and bolstered wealth. As oligarchs, they demanded L’Enfant’s dismissal. Forced to choose between lucre and virtue, the father of our country—whose fortunes sprang from speculation in Indigenous lands and bonded slavery—predictably acquiesced.

As a result, the high court remained sequestered inside the U.S. Capitol until the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt—144 years later.

The Civil War transformed Judiciary Square into a theater of carnage. Wounded troops from the Army of the Potomac overwhelmed the city hospital adjacent to the square’s grassy three acres. After a fire destroyed it, residents objected to a military replacement, distressed by the interminable sight and odor of corpses lying in the open air.

The numbers of wounded grew so large that the government commandeered City Hall (now the U.S. District Court of Appeals), the Patent Office (now the National Portrait Gallery), and the National Mall to accommodate them, thus elevating Judiciary Square as a site of memory in the war-time capital.

On the third anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, 20,000 people gathered there in pouring rain to witness the unveiling of the martyred president’s first statue. Lincoln stands today gesturing toward both the Capitol and, as if mocked, toward General Pike, a mere block away.

The Pension Building, now the National Building Museum, rose on the square’s northern boundary in 1887, a colossus built by Montgomery C. Meigs, the Army’s Quartermaster General. Inspired by the Palazzo Farnese, Meigs wrapped his adaptation in a 1,200-foot-long plastered frieze depicting Union soldiers, sailors, and laborers, Black and white, in motion, on the march.

The 1,500 clerks who processed the claims of Union veterans required large quarters, but Meigs, an ardent abolitionist, intended that the Pension Building convey the magnitude of brute strength and sacrifice summoned to smash the Slave Power.

Meigs’ frieze is the closest thing we have in Washington to a national monument to Union victory, but its understatement redounds to de facto obscurity.

And if not for preservationists, it would have fallen to the wrecking ball decades ago.

As white southerners filled their ruined landscapes with war memorials, the Republican Party indulged in Gilded Age gluttony—as it does today—leaving Judiciary Square fallow, its ground having so recently borne the bodies whose sacrifice bequeathed the nation’s prosperity.

By 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt’s pursuit of imperialism among “the darker races” of the Caribbean and Pacific had reunited former white Unionists with their erstwhile Confederate enemies. Thus did the reactionary winds of American white supremacy clear space at Judiciary Square for General Pike. That year, as vigilantes lynched dozens of Black Americans, Pike’s devotees claimed to honor his attenuated legacy as Sovereign Grand Commander of the Scottish Rite of Freemasons, Southern Jurisdiction, its obsession with secrecy, ritual, and hierarchy having been birthed in the slaveholder’s bastion of Charleston.

As if one can slice and dice a life that way. As if southern Freemasonry has a redemptive function in a democratic society.

Steps away from General Pike is the national law enforcement memorial whose martyrs include southern police vigilantes—Pike’s natural allies—who enforced the brutality of Jim Crow, led lynch mobs, and wore the hood of the Klan. Sheriff Henry Howard of Aiken, South Carolina, is among its many chiseled names. His vigilante victims included two teenage boys, a woman, and two young men.

Adding insult to injury, Howard and other Jim Crow cops are honored on ground where the moldering bodies of Union soldiers once lay stacked, their lives given to vanquish the forces of reaction now memorialized there instead.

Meigs’s frieze looms over the police monument and its adjacent $80M saccharine law enforcement museum—a mute rebuke to this betrayal.

Why does history matter?

Instead of the U.S. Supreme Court we have a monument that hails the shock troops of apartheid and the defense of private property. In place of a memorial to the Union dead, we have a statue of a Confederate general.

There is nothing “judicious” about Judiciary Square, but there is a dark honesty about the place. The shadow theory of psychoanalyst Carl Jung is instructive as we survey its monumental architecture. With memorials to a two-bit Confederate general and killer cops taking center stage, the delusional mythos that ours is a nation guided by high principle is thoroughly discredited.

Despite our vehement denial, we are a nation deeply reverential of Manifest Destiny—its bloody slaughter, dehumanization, and degradation papered over with lying mantras like, “All men are created equal,” and “Liberty and justice for all”—even “America the Beautiful.”

Judiciary Square, then, is a place of frank if ugly truth-telling. The sooner we recognize our true collective nature—personified in spades by Donald Trump—the quicker we might get on with the work of transformation.